Funds Transfer Pricing (FTP) has become a hot topic again as the recent interest rate volatility has sent shock waves through financial institutions (FIs). FTP is a great tool for measuring and managing elements of interest rate risk that most ALM systems simply can’t do. Simultaneously, it is critical for understanding where value is created or destroyed in the FI. It is equally important as an input to pricing loans and deposits to reflect embedded interest rate risk. However, many simply don’t understand the basics of FTP and how it can benefit the FI. This paper outlines those basics and the power of understanding this knowledge.

The fundamental concept behind Funds Transfer Pricing (FTP) is the classic buy versus make accounting theory. The raw materials for an FI are funding while the finished products are assets. What FTP fundamentally does is look at what it costs to “buy” similar funding from wholesale markets such as brokered CDs, FHLB advances, etc., and compares that to “making” or “gathering” funds from the FI branch system.

The comparison is not just rate to rate. It is understanding the rate PLUS the cost of acquisition and servicing. Making internal funding can cost 30-50 basis points in addition to the rate paid on the deposits. Wholesale funding transaction and servicing costs are virtually nothing in most cases.

FIs can generally raise funding through their branch networks at noticeably less than wholesale fund's all-in costs. The difference between the all-in wholesale funding costs and the funding raised by the FI’s branch network is the equivalent to the benefit of making raw material versus buying it. That differential is the fundamental value of one’s deposit-gathering operations. This can be a significant competitive advantage that high performance FIs understand.

To do this properly there are a few rules of modern fixed-income portfolio analytics and basic “buy versus make” concepts of accounting that must be followed. First the buy versus make rules.

In this concept, the first rule is that of your college Accounting and Economics 101 concept of marginal costing. Marginal costing means that the cost to obtain raw material must be measured against TODAY’S costs, not yesterdays. A manufacturer that bases its costs on last year’s costs will get killed in an inflationary environment and so will a financial institution. This means that an FI’s internal cost of funds, being a historical measure of what funds used to cost, is not appropriate for this analysis.

Next, these costs must be compared to similar types of instruments. A common way to measure similarity between financial instruments is to determine the duration or weighted average life. Simply, a wholesale funding with a duration of two years should be compared to a CD of also a two-year duration. As stated before, the difference between the all-in cost of the wholesale funding versus the all-in cost of the retail deposits is the marginal value your deposit operations contribute to the overall value of the organization. Now that we have defined how to value deposits, lets discuss how this applies to lending.

Funding costs are a major piece to understanding the cost to originate and service loans and the same principles should apply. The wholesale funding rate was used to understand the value of deposits and therefore becomes the assumed cost of funds for pricing loans. This process separates the value of loans from the value of deposits so one can see the core value created for each side of the balance sheet.

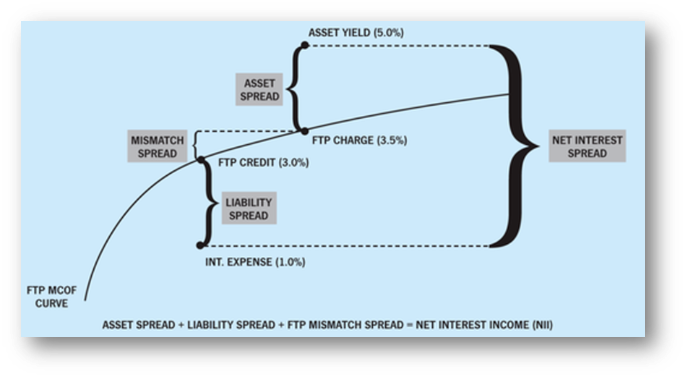

So, following the two prior rules, the cost of funds for a two-year duration asset should be the wholesale funding costs for a two-year duration borrowing. Not matching durations systematically introduces interest rate risk which any further discussion is beyond the scope of this article. It is the “Mismatch Spread” in the following chart.

A major mistake many FIs make is to use their internal average cost of funds as an input for the funding cost for a loan. As explained before, this violates the marginal costing paradigm as the average cost of funds is a historical measure and does not reflect the current marginal cost to originate a new loan.

Using one’s traditional internal cost of funds assumes all value is created by loans and none from deposits. It does this by ignoring the value of deposits identified by the FTP process. It says liabilities are just costs and nothing more. FIs inherently understand that they are nothing without deposits so they must create some measurable value. FTP enables one to measure that value.

What stuns many is that after this exercise it is common to find that the deposit side of the balance sheet creates more value than the lending. Sometimes a lot more. As surprising as that sounds, it should not be as there is plenty of comparative evidence. As of his writing (January 2023), everyone knows that FinTechs are clamoring for your deposits and not for your loans. In fact, if you are holding loans with a coupon under 7% the market value of those loans is underwater meaning your entire asset base is worth less than the amount you loaned out. For example, 4.50% coupon auto loans are trading around 95-96.

In contrast, everyone would love to get their hands on your cheap deposits. With the average industry cost of funds being around 0.65% and the cost of similar wholesale funding at around 4.25% who wouldn’t want your deposits? In the mergers and acquisition world, deposit bases are going for 110 or 10% premiums. Now compare that to the 95-96 price or a 5% discount for auto loans.

So, why shouldn’t your profitability analytics reflect these realities? Understanding what truly drives value in an FI is critical to outperforming the industry average. FTP is just the tool that helps identify which products, customers/members, credit scores, account officers, etc. create and destroy value. Knowing this enables one to promote what you do well and fix what isn’t working.